Miraal Mavalvala

This blog is based on learnings from the development of the “Family Planning Service Delivery Strategy for Northern Nigeria” designed by Impact for Health International for The Society for Family Health in Nigeria under the FCDO-funded Lafiya project.

Context

As countries advance progress towards UHC 2030 goals, it is crucial that the global community advocate for the inclusion of quality family planning (FP) and other reproductive health (RH) services within UHC schemes to promote equity and access to FP/RH services.

Figure 1: Health spending as a share of total

government expenditure in Nigeria.

The UHC movement has laid particular emphasis on domestic resource mobilisation exemplified by the 2011 Abuja Declaration target of 15% government budget allocated towards health. (1) Ten years on, Nigeria is far from achieving this goal with health expenditure recorded at approximately 2.2% as a share of total government expenditures in 2017. (2) (Figure 1)

Challenges

Low coverage rates of basic health services largely drive poor health outcomes, and Nigeria’s health outcomes are among the poorest in the world – the nation’s high maternal mortality rate accounts for nearly 14% of the global burden of maternal deaths,(3) largely resulting from preventable complications such as unsafe abortions (which attribute 11% of maternal deaths).(2)

Figure 2: Share of health expenditure covered by OOP payments, government and donors (level of OOP in Nigeria is the highest in SSA)

Access to quality FP services by Nigerians has been hindered by financial barriers, particularly high out of pocket expenditures (67% costs paid out-of-pocket (OOP), while 26% is paid by the government and 7% by development partners).(2) Further, the country suffers from an overall lack of smart, scaled and sustainable financing mechanisms for FP services that encompasses both the public and private sectors. (Figure 2)

Solution

To address the situation, the Government of Nigeria has demonstrated political and financial will towards UHC as represented by the 2014 National Health Act (NHA). Through the NHA, Nigerians are entitled to the Basic Minimum Package of Health Services (BMPHS) covered by the Basic Healthcare Provision Fund (BHCPF) which is funded by a minimum of 1% of consolidated federal government revenues.

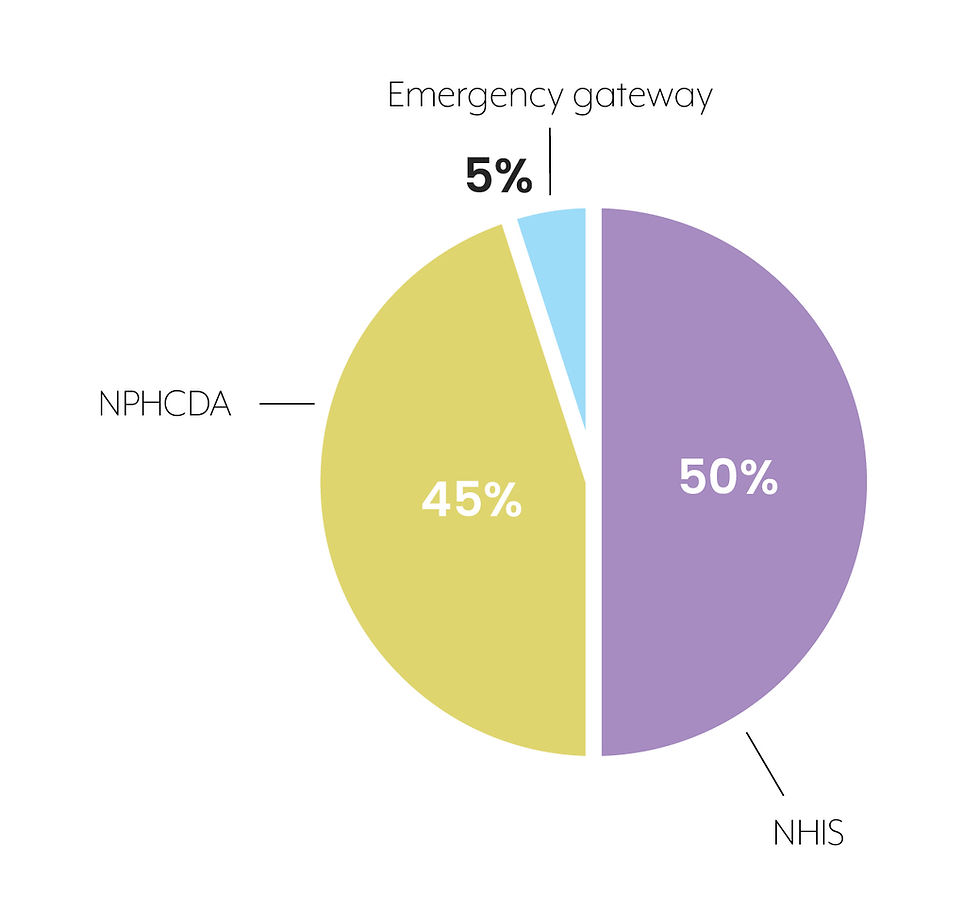

Figure 3: Distribution of funding pathways for the BHCPF

50% of BHCPF funds are allocated through the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) gateway, 45% through the National Primary Healthcare Development Agency (NPHCDA) and the remaining 5% through the emergency gateway. (Figure 3)

Importantly, FP commodities including pills, condoms, injectables and implants are included within the BMPHS.(2) Inclusion of FP services within UHC schemes can improve access to and uptake of modern FP methods, as seen in a study that assessed FP-inclusive health insurance schemes in Latin America and Caribbean countries and found that insured women among the poorest quintile had a higher mCPR to those that were uninsured.(4)(5)

Integrating quality of care within BHCFP

However, advocacy efforts for FP services within the UHC agenda goes beyond mere “inclusion” – it should simultaneously stress the integration of quality of FP/RH care within UHC schemes. And indeed, that is what Nigeria’s BHCPF program strives to do. The 2020 revised BHCPF guidelines have introduced additional eligibility requirements for state participation in the program with particular emphasis on quality of services.(6) For example, to receive funds through the NHIS gateway, health facilities providing FP services must meet the following quality standards:

Accreditation and empanelment of primary healthcare and secondary health facilities by the State Health Insurance Agency.

Service level agreement with accredited facilities.

Similarly, for disbursement of funds through the NPHCDA gateway, facilities must meet the following eligibility requirements:

Baseline assessments must be conducted of health facilities

PHC facilities must submit annual quality improvement plans

Figure 4: Routine BHCPF facility quality improvement score card

*Adapted from the BHCPF 2020 Guidelines for Nigeria

Scorecards will be generated based on a quality improvement assessment to measure facility level performance across 10 priority areas (elements of FP/RH services included within MCH services). (Figure 4)

The national gateways also play a very strategic role in governance of the scheme – for example, the NPHCDA is responsible for the development of regulations and standards for PHC facilities while the NHIS is responsible for contracting accredited healthcare providers for service provision.

Going Forward

As Nigeria considers possible expansion of FP/RH services within the BHCPF program, stakeholders must not lose sight of the quality-of-care component. Appleford, RamaRao and Bellows propose a framework that governments may refer to for guidance on SRH service integration within national health insurance schemes.(7)

Figure 5: The "5 Ps" Framework

The “5 Ps” Framework describes a practical approach to integrate quality of SRH care within UHC schemes, emphasizing a “systems and design” lens as important steps to quality.(7) The framework address the following: i) People: for whom to purchase, ii) Package: what to purchase, iii) Provider: from whom to purchase, iv) Payment: how to purchase, and v) Polity: why purchase. In doing so, the framework also highlights the need to design SRH purchasing strategies from a rights-based perspective ensuring that SRH services are universally available, accessible and acceptable.

If quality of SRH care is successfully integrated into Nigeria’s BHCPF program, the Nigerian people will not only benefit from coverage of essential SRH services but also enjoy maximum health impact from enhanced quality.

*Implementation of BHCPF is already at various stages in thirty States of the Federation.

References

[1] Musango, Laurent, et al. "The state of health financing in the African Region." Health Monitor 16.9 (2013).

[2] Global Financing Facility. Federal Government of Nigeria, 2017. Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health and Nutrition 2017-2030 Investment Case.

[3] Federal Government of Nigeria. 2018. National Demographic and Health Survey.

[4] Fagan, Thomas, et al. "Family planning in the context of Latin America's universal health coverage agenda." Global Health: Science and Practice 5.3 (2017): 382-398.

[5] Appleford, Gabrielle, and Saumya RamaRao. "Health financing and family planning in the context of universal health care: connecting the discourse." (2019).

[6] Nigeria Federal Ministry of Health. 2020. Guideline for the administration, disbursement and monitoring of the Basic Healthcare Provision Fund. Available at: https://www.health.gov.ng/doc/BHCPF-2020-Guidelines.pdf

[7] Appleford, Gabrielle, Saumya RamaRao, and Ben Bellows. "The inclusion of sexual and reproductive health services within universal health care through intentional design." Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters 28.2 (2020): 1799589.

コメント